Un inolvidable y necesario filme de Margarethe von Trotta (Esp | Eng)

ESP

Hace dos días publiqué un post sobre el filósofo alemán Karl Jaspers (*), y en él citaba a una de sus caras discípulas, Hannah Arendt, estimada como la filósofa más importante del siglo XX, autora de un pensamiento de suma trascendencia acerca del ser humano, su condición moral, ética, política e histórica. Sobre ella publiqué un post el año pasado, que pueden ver aquí.

Pero este post no trata centralmente sobre Hannah Arendt, sino sobre la cineasta, también alemana, Margarethe von Trotta , a quien pensé dedicar una publicación tomando en cuenta su nacimiento, el 21 de febrero de 1942, que realizara en 2012 un filme sobre la filósofa mencionada, objeto de este post.

ENG

Two days ago I published a post about the German philosopher Karl Jaspers (*), and in it he cited one of his beloved disciples, Hannah Arendt, considered the most important philosopher of the century XX, author of a thought of utmost importance about the human being, his moral, ethical, political and historical condition. I published a post about her last year, which you can see here.

But this post is not primarily about Hannah Arendt, but about the filmmaker, also German, Margarethe von Trotta , to whom I thought I would dedicate a publication taking into account her birth, on February 21, 1942, which was made in 2012 in the film about the aforementioned philosopher, the subject of this post.

Margarethe von Trotta es quizás la más destacada cineasta alemana de la segunda mitad del siglo XX hasta nuestros días, que se asocia con el llamado "Nuevo cine alemán", surgido en la década del 60 y donde se incluyen a famosos directores, como Fassbinder, Schlöndorff, Herzog y Wenders.

Su cine se ha centrado en figuras femeninas de relevancia, como una forma de abordar el tema de la mujer y su función en la sociedad, desde una amplia visión. De los pocos filmes que he podido ver, destaco Las hermanas alemanas (1981), Rosa Luxemburgo (1986) y Hannah Arendt (2012).

El último de ella que pude ver es el dedicado a la filósofa judío-alemana mencionada, el cual fue titulado comercialmente en español como Hannah Arendt y la banalidad del mal , añadido al original que me pareció muy pertinente, pues podría llamar la atención de aquellos que no conocieran a esta sin par mujer.

Margarethe von Trotta is perhaps the most prominent German filmmaker of the second half of the 20th century to the present day, who is associated with the so-called "New German Cinema", which emerged in the 1960s and includes names such as Fassbinder, Schlöndorff, Herzog and Wenders. Her films have focused on relevant female figures, as a way of addressing the issue of women and their function in society, from a broad perspective. Of the few films that I have been able to see, I highlight The German Sisters (1981), Rosa Luxemburg (1986) and Hannah Arendt (2012).

The last one of hers that I was able to see is the one dedicated to the aforementioned Jewish-German philosopher, which was commercially titled in Spanish as Hannah Arendt and the banality of evil , added to the original which seemed very pertinent to me, as it could draw the attention of those who did not know this peerless woman.

¿De qué trata este filme? De la controversial experiencia -vital e intelectual- de Hannah Arendt, que ya dijimos que era de origen judío, para emitir su juicio ante la motivación de la conducta de un criminal de guerra nazi y la "normalidad" de esa actuación.

Arendt, quien ya había sufrido por su condición de judía e intelectual durante el nazismo en Alemania y Francia, invadida por este, se había residenciado en EEUU en 1941, con su esposo Heinrich Büchler. En 1961, cuando fuera atrapado el criminal nazi Adolf Eichman, se propone como periodista para asistir al juicio en Jerusalén y escribir los artículos respectivos para la revista The New Yorker, que aparecieron paulatinamente, y luego se convertirían en el libro Eichman en Jerusalén en 1963.

Esta sería la anécdota básica del filme ficcional, con base biográfica, dirigido por Margarethe von Trotta, con guion suyo, basado en el libro de Arendt, por supuesto. Sabe destacar la directora alemana el conflicto interior vivido por el personaje, la filósofa Arendt, en relación con la historia inmediata de horror experimentado por judíos y muchos otros, y el tratar de comprender qué anima aquella mente del criminal Eichman. El planteamiento central que deja Arendt en su libro es el que, con delicadeza y precisión, nos entrega von Trotta: se puede ejercer el mal, ser su ejecutor principal, y asumir que sólo se cumplen órdenes, que la actuación es un resultado de la obediencia, algo "normal", pues se es solo un administrador, un burócrata. Acentúa la cineasta el sentido de la "ausencia del pensar" en Eichman, pues no reflexiona sobre lo que hace. Es lo que llama banalidad del mal

Pero también es importante en el filme cómo se mantiene la actitud de incomprensión, hasta la condena y persecución, de Arendt por parte de otros intelectuales judíos, de académicos, de amigos, de toda una sociedad de su época.

Traer este complejo asunto a nuestra consideración, especialmente a aquellos que no han leído a Arendt, es uno de los valores del filme de von Trotta.

What is this film about? Of the controversial vital and intellectual experience of Hannah Arendt, who we already said was of Jewish origin, of issuing her judgment regarding the motivation for the behavior of a Nazi war criminal and the "normality" of that action.

Arendt, who had already suffered because of her Jewish and intellectual status during Nazism in Germany and France, invaded by it, had resided in the United States in 1941, with her husband Heinrich Büchler. In 1961, when the Nazi criminal Adolf Eichman was captured, he proposed as a journalist to attend the trial in Jerusalem and write the respective articles for the magazine The New Yorker, which appeared gradually, and would later become the book Eichman in Jerusalem in 1963.

This would be the basic anecdote of the fictional film, with a biographical basis, directed by Margarethe von Trotta, with her script, based on Arendt's book, of course. The German director knows how to highlight the internal conflict experienced by the character, the philosopher Arendt, in relation to the immediate history of horror experienced by Jews and many others, and trying to understand what animates the mind of the criminal Eichman. The central approach that Arendt leaves in her book is the one that, with delicacy and precision, von Trotta gives us: one can exercise evil, be its main executor, and assume that only orders are followed, that the action is a result of obedience, something "normal", since one is only an administrator, a bureaucrat. The filmmaker accentuates the sense of "absence of thinking" in Eichman, since she does not reflect on what he does. It is what she calls banality of evil.

But it is also important in the film how Arendt's attitude of incomprehension, even condemnation and persecution, is maintained by other Jewish intellectuals, academics, friends, an entire society of her time.

Bringing this complex issue to our consideration, especially to those who have not read Arendt, is one of the values of von Trotta's film.

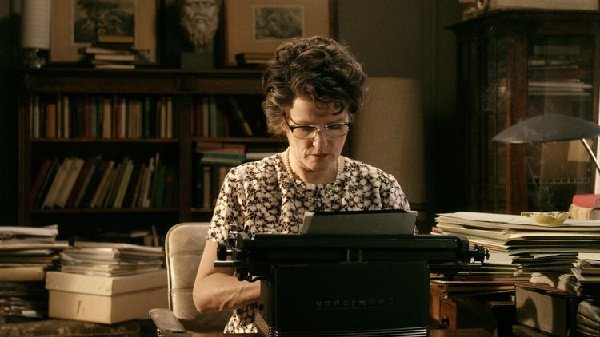

Todo ello lo logra con un eje: la expresiva y magnífica interpretación de la actriz alemana Barbara Sukova, que caracteriza al personaje histórico con toda la profundidad psicológica (nerviosismo, ansiedad, afectividad, duda, etc.); a lo que contribuye un maquillaje y vestuario muy acertado. También el uso inteligente de fragmentos de las grabaciones del juicio, donde ocupa una función clave el enfoque en Eichman, aparte de otros testimonios. Igualmente las actuaciones de los que hacen de su esposo, amigos y su maestro Martin Heidegger.

La fotografía es de gran nitidez y con uso apropiado de los planos, en particular aquellos donde podemos apreciar la emoción del personaje, muchas veces casi ataráxica. También cabe resaltar el uso del sonido, manifestándose como silencio o por la sugestiva música de André Mergenthaler.

He achieves all this with one axis: the expressive and magnificent performance of the German actress Barbara Sukova, who characterizes the historical character with all the psychological depth (nervousness, anxiety, affection, doubt, etc.); to which very accurate makeup and costumes contribute. Also the intelligent use of fragments of the trial recordings, where Eichman's crosshairs play a key role, apart from other testimonies. Likewise the performances of those who play her husband, her friends and her teacher Martin Heidegger.

The photography is very clear and with appropriate use of shots, particularly those where we can appreciate the emotion of the character, often almost ataraxic. It is also worth highlighting the use of sound, manifesting as silence or the suggestive music of André Mergenthaler.

Recomendaría que, todos los que puedan, vean este filme de Margarethe von Trotta. Por supuesto, no es un estilo en la onda de lo que les gusta a la mayoría de nuestros jóvenes actuales. Quizás algunos se escapen de esa tabla rasa. Se trata de un filme que, no habiendo leído a Arendt, no sólo nos acerca a su pensamiento capital para la modernidad, sino más aún, nos puede abrir los ojos o alertar sobre esa "banalidad del mal" que nos rodea.

I would recommend that everyone who can see this film by Margarethe von Trotta. Of course, it is not a style in line with what most of our current young people like. Maybe some will escape from that blank slate. It is a film that, not having read Arendt, not only brings us closer to her capital thought for modernity, but even more can open our eyes or alert us to that "banality of evil" that surrounds us.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margarethe_von_Trotta

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margarethe_von_Trotta

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt

You dropped this post on the Pinmapple Discord a while ago. Pinmapple is a travel community and the server room clearly says No link dropping allowed. Pleae go back to delete the link. Thanks

Me alegra saber de esta película. Eichman en Jerusalén, creo que es uno de los libros menos conocidos de Hannah Arendt y la polémica que acompañó al libro creo que es todavía más desconocida. Con motivo del juicio a Eichman, Hannah Arendt, en su disección del autoritarismo, dio un paso más allá. Si no recuerdo mal, la tesis central del libro es que cualquier organización que colabore, en una u otra medida, con un régimen totalitario se vuelve incapaz de ejercer cualquier oposición a éste, incluso si busca el mal menor. En este caso, el dedo acusador de Hannah Arendt señaló al Consejo Judío por su colaboración con el nazismo y las consecuencias en vidas humanas de esta colaboración. De ahí, la polémica del libro. Un saludo @josemalavem y gracia por esta reseña

Hola, @enraizar. Esa es una de las ideas expuestas en el libro, pero no la central. La principal es, precisamente, la banalidad del mal, que supongo conoces su planteamiento al respecto. Yo lo sintetizo en el post. Saludos.

Hola, tienes razón @josemalavem, otra vez. Me expresé mal, creo que la idea de la banalidad del mal ya está expuesta en sus dos trabajos anteriores. Lo que quiero subrayar es que el debate abierto con el libro se corresponde con ese paso más allá que se da en este texto. Así lo recoge también Bruno Betthelheim, comentando el trabajo de Hannah Arendt, en su libro Sobrevivir, donde subraya como en el propio juicio parte del público, víctima de los campos de exterminio, acusó de colaboradores a algunos de los líderes judíos que participaron como testigos. A mi este aspecto de la colaboración me sigue pareciendo importante hoy en día, pero eso ya es una opinión. Un abrazo muy grande y gracias por la respuesta.