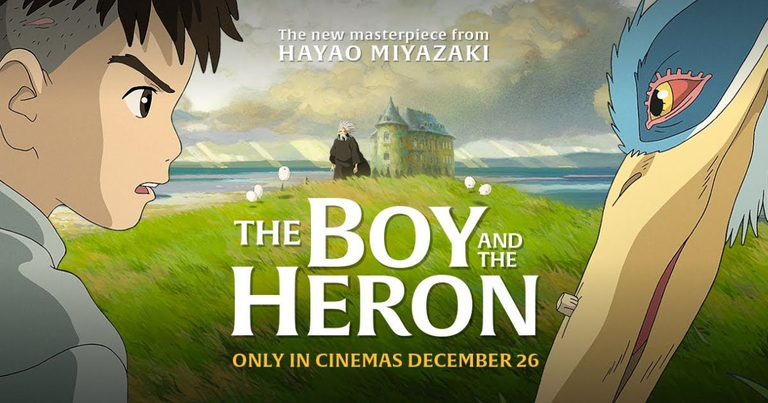

Mastermind reviews: The Boy and the Heron

The infinite magnificence of the Japanese master can never be reduced to mere logic, and this movie serves as a reminder of why we should live. But who is this elderly man fighting to save the world below, that magical cosmos that evokes a different dimension full of ghosts and the dead, as well as hopes, dreams, promises, and memories? Who is that insane great-uncle searching for a blood relative to succeed him and bring about the creation of a planet worthy of being a beautiful place to live? Is Miyazaki actually the author? Additionally, it appears that the Maestro has chosen to shoot another movie to give his nephew a message after repeatedly announcing his retirement. Similar to how Mahito's mother sends her son a narrative to read when he passes away, asking, "And how will you live?" The original title of The Boy and the Heron is Kimi-tachi wa dō ikiru ka, which is also the title of a coming-of-age novel written by Genzaburō Yoshino and served as a major inspiration for Miyazaki's most recent film. which means that it may actually resemble a handover and a farewell message. However, it is more than just the painful awareness that a succession is impossible. which recognizes the challenge of maintaining an increasingly antiquated production concept, a method, and a way of perceiving animation. Do we still recall the ox-drawn planes from The Wind Rises? How quickly is this movie theater adapting to the demands and fresh approaches of the industry? The Boy and the Heron took seven years to finish. Isn't the lowering phase of the parable now upon us, unavoidably, if the creative life peaks after ten years? This appears to be the most reasonable explanation. Epigones are not allowed in a piece of art this intimate, an imaginative cosmos with distinct personalities and features that are easily recognizable. Everything is meant to come to a conclusion and run its course with the writer.

Still, still, still... It is impossible to reduce Miyazaki's unending genius to mere reasoning. It would seem, then, that his deep spirit finds a more genuine identity in Mahito, the youngster who comes to know life. It is no accident that Miyazaki's father was an aeronautical engineer, just like his young protagonist's. It's also possible that it's a logical continuation of The Wind Rises, with the character picked up again later on, outside of the grief and from a new angle. To put it briefly, we are aware of the typical obsessions: flight, literature, airplane caps, conflict and the fear of self-destruction, fire, and the sheer beauty of shapes. Just as the routes diverge and the traces grow in number, the shadow play is further complicated by projections and reflections. And in the game of perspectives, it seemed as though Mahito's other theory—his future self—was this insane old great-uncle, this helpless god, in the event that the boy decided to stay in the other realm indefinitely.

After all, the movie is replete with scenes of sleep and dreams, abrupt awakenings, and features that blur and become less distinct when heat waves from a fire or memory mists appear. Similar to the first fire, where Miyazaki reaches complete emotional force and the animation appears to depict a parade of ghosts. However, memories, dreams, prophecies, and projections are only forms of the mind. They are part of the current time's density. If the world below is indeed a descent into the unconscious, then it is compelled to carry out its tasks, make its way back to light, adjust consciousness's set course, force it to overcome its obstacles, and begin anew from scratch. In the same way that it is impossible to permanently flee, to shut oneself in a virtual world where one plays with the parts of the machine every day, or to fool oneself into believing that there is a new, ideal equilibrium. No, we have to go back to this other side all the time, where things aren't perfect but, in between the light and shadow, things are molded and their forms are carved, and everything is found—if not harmony, then at least a sense. If spirits exist everywhere and the gods are everywhere, then every action and decision—even the most routine and unremarkable—is an homage to this divine reality. We must thus continue to live. You're still alive! Exactly what Naoko says to Jiro in The Wind Rises' climax. And Miyazaki has consistently informed us of this. It makes no claims to provide us with instructions on how and why to accomplish anything. However, every one of his movies is an unwavering testament to the urgency of our time and our will to live. In spite of everything. And nothing else is required.

Vote 9/10

I'm really looking forward to seeing this movie, it looks great!

Salu2 😎

You will like it!