Film Review: Zabriskie Point (1970)

By the 1960s, Michelangelo Antonioni had become a lodestar of arthouse cinema, his name synonymous with existential alienation and modernist formalism. His reputation transcended cinephile circles, even permeating pop culture: the 1968 countercultural musical Hair name-dropped him in its lyrics, cementing his status as a Boomer-era icon. This acclaim peaked with Blow-Up (1966), a defining portrait of Swinging London that blended mystery and ennui to critical and commercial success. Emboldened, Antonioni sought to replicate this alchemy with Zabriskie Point (1970), a kaleidoscopic exploration of California’s counterculture. The result, however, was a paradoxical disaster—a film both fascinating and flawed, dismissed upon release yet impossible to ignore. As Roger Ebert bluntly declared, it was “a silly and stupid movie” burdened by ideological posturing , yet its audacious visuals and cultural ambition render it a compelling relic of its time.

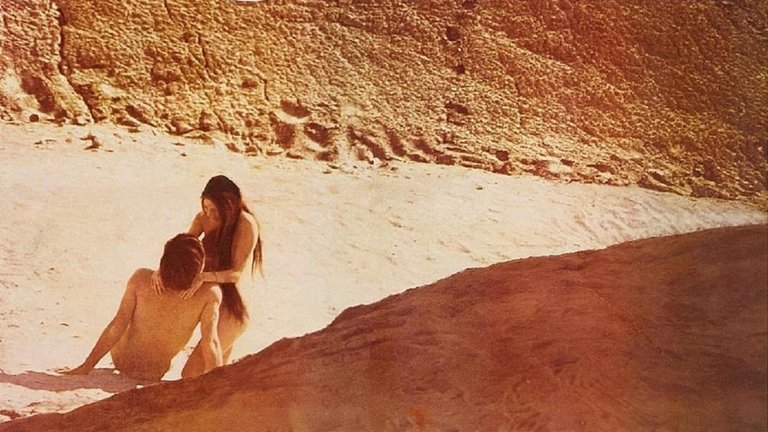

The film’s protagonists embody the era’s fractured idealism. Mark (played by Mark Frechette), a disaffected forklift operator and college dropout, drifts between radical student protests and nihilistic escapism. After a police crackdown leaves him implicated in an officer’s death, he steals a plane and flees Los Angeles, symbolically “getting off the ground” to escape societal constraints. His counterpart, Daria (played by Daria Halprin), a secretary entangled with her real-estate mogul boss Lee Allen (played by Rod Taylor), abandons the city to seek a nebulous freedom in the desert. Their paths converge at Zabriskie Point, where they engage in a surreal lovemaking ritual amid dust clouds and anonymous couples—a sequence Antonioni intended as a metaphor for collective liberation . Yet Mark’s decision to return the plane, culminating in his death at the hands of police, and Daria’s hollow arrival at Allen’s mansion underscore the film’s nihilistic core: rebellion dissolves into futility, leaving only alienation in its wake.

Produced by MGM—a studio synonymous with Hollywood’s golden age—Zabriskie Point epitomised the industry’s clumsy attempts to court the Boomer demographic. The studio greenlit Antonioni’s project after Blow-Up’s success, hoping to capitalise on anti-establishment sentiment. Instead, the film’s critique of consumerism and authority proved too abstract for mainstream audiences, while its non-linear structure baffled executives accustomed to conventional narratives. Antonioni’s vision clashed with Hollywood’s commercial instincts, resulting in a $7 million budget yielding a mere $1 million return—a catastrophic flop that exposed the generational chasm between Old Hollywood and the New Left .

The screenplay, co-written by Antonioni, Sam Shepard, and others, drew loose inspiration from Hail Thomas Hansen, a young man who stole a plane in 1967 and was killed upon landing . Yet this kernel of realism is buried beneath layers of symbolism. The opening student protest, filmed in vérité style, captures the era’s radical energy, with Black Panther activist Kathleen Cleaver playing a fictionalised version of herself. However, the narrative quickly fractures into impressionistic vignettes: Mark’s gun purchase satirises America’s lax firearm laws , while Lee Allen’s dystopian real estate ads—featuring mannequins in sterile homes—lampoon capitalist excess. These fragments, though visually striking, lack cohesion, reducing the protagonists to ciphers rather than fully realised characters.

Where the script falters, Antonioni’s directorial brilliance salvages moments of transcendence. Cinematographer Alfio Contini bathes Death Valley in stark, hallucinatory hues, transforming the desert into a metaphysical landscape. The telephoto lens, a Antonioni trademark, flattens space to evoke emotional isolation, while the final explosion of Allen’s mansion—a slow-motion ballet of disintegrating consumer goods—remains a tour de force of practical effects. Even the much-maligned “orgy” scene, with its writhing bodies and Pink Floyd score, aspires to mythic resonance, though it ultimately succumbs to pretentious abstraction.

Antonioni’s insistence on “authenticity” led him to cast non-actors Frechette and Halprin, whose off-screen romance mirrored their on-screen dynamic. While their raw presence suited the film’s anti-Hollywood ethos, their performances—halting, inexpressive—exposed their inexperience. Frechette, in particular, struggled with dialogue, his line deliveries often wooden. Antonioni’s gamble backfired: audiences found the leads implausible, exacerbating the film’s emotional detachment .

The soundtrack, featuring Pink Floyd, The Rolling Stones, and Jerry Garcia, should have been a countercultural crescendo. Instead, the music feels ancillary, its potential diluted by abrupt edits and tonal mismatches. Pink Floyd’s contributions, though haunting, are underutilised, while the climactic explosion—scored to “Come in Number 51, Your Time Is Up”—achieves grandeur but cannot salvage the preceding incoherence .

Zabriskie Point’s 1970 release was a perfect storm of failure: scathing reviews, public indifference, and Frechette’s vocal disdain for the project . Its inclusion in The Fifty Worst Films of All Time (1978) cemented its reputation as a pretentious misfire . Yet, like many maligned works, it has undergone reassessment. Contemporary critics praise its audacious visuals and prescient critique of consumerism, though its narrative flaws remain insurmountable .

Zabriskie Point is less a film than a archaeological artefact—a time capsule of late-’60s disillusionment. Antonioni’s ambition to capture America’s “essential truths” resulted in a work as fragmented as the era it depicts. Its images linger, but its soul remains elusive, a testament to the chasm between European arthouse introspection and Hollywood’s commercial imperatives. As Antonioni himself conceded, the film was “not a revolutionary picture” , merely a flawed, feverish dream of rebellion—one that resonates precisely because it dares to fail so spectacularly.

RATING: 4/10 (+)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Posted Using INLEO