Film Review: Five Easy Pieces (1970)

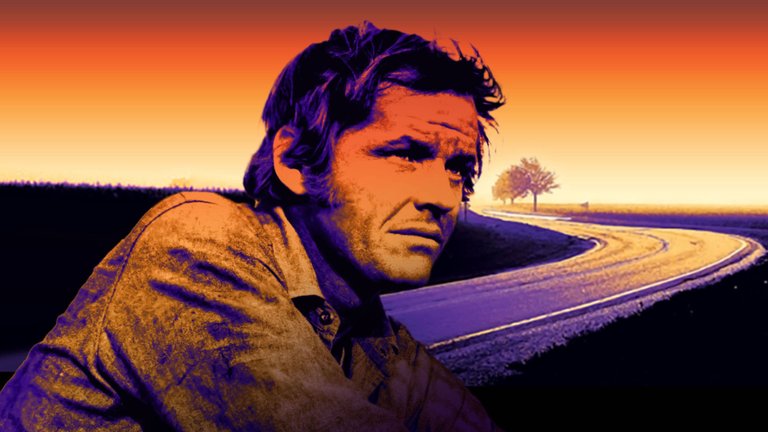

If there is a single genre emblematic of the New Hollywood era, it is the road film—a cinematic form that mirrored the existential wanderlust and societal disillusionment of post-1960s America. Few actors embody this movement’s spirit as indelibly as Jack Nicholson, whose meteoric rise to stardom in the early 1970s was cemented by his role in Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces (1970). A quintessential road movie, the film follows the fractured journey of Bobby Dupea, a man adrift between social classes and identities, whose restless mobility reflects the era’s cultural upheavals. Nicholson’s magnetic performance here not only solidified his status as a leading man but also captured the zeitgeist of a generation grappling with fractured ideals.

Nicholson’s Bobby is introduced as a blue-collar oil rig worker in California, living with his girlfriend Rayette Dipesto (played by Karen Black), a waitress whose devotion to Tammy Wynette’s ballads underscores her simplicity. Their life—filled with bowling, beer, and casual infidelity—initially seems unremarkable. Yet, the film gradually peels back layers of Bobby’s past, revealing his origins in an affluent family of classical musicians. When his sister Partita (played by Lois Smith) informs him of their father’s terminal illness, Bobby reluctantly travels to the family’s isolated Puget Sound estate, dragging Rayette—now pregnant—along as an uncomfortable companion. There, he confronts his brother Carl (played by Ralph Waite) and is drawn to Catherine (played by Susan Anspach), a poised pianist whose intellectual allure highlights Bobby’s self-imposed alienation.

Five Easy Pieces functions as a spiritual sequel to Easy Rider (1969), another countercultural touchstone produced by Rafelson’s BBS Productions. Both films share a producer (Rafelson), cast members (Nicholson and Karen Black), and a narrative framework rooted in itinerant rebellion. However, while Easy Rider mythologised the open road as a symbol of freedom, Five Easy Pieces subverts this idealism, presenting mobility as a futile escape from existential paralysis.

The film interrogates the chasm between Bobby’s generation and the rigid traditions of his upbringing. His father (played by William Challee), a silent, stroke-ridden patriarch, symbolises an unyielding legacy of artistic excellence that Bobby has rejected. Yet, his rebellion is not a triumphant embrace of counterculture but a hollow act of self-sabotage. Unlike the romanticised hippie nomads of Easy Rider, Bobby’s defiance is rooted in resentment and inadequacy, a refusal to conform that leaves him stranded between worlds.

Rafelson’s film diverges sharply from its predecessors by framing rebellion as a symptom of dysfunction rather than liberation. Bobby’s flight from responsibility—whether abandoning Rayette or shirking his musical talent—exposes a profound emotional immaturity. His attempts to “discover himself” are marked by self-loathing and a penchant for cruelty, epitomised in the infamous diner scene where he berates a waitress over a chicken salad sandwich. Nicholson’s genius lies in rendering this deeply flawed character compelling, infusing him with vulnerability beneath the abrasive exterior.

Without Nicholson’s layered performance, Five Easy Pieces risks collapsing under its narrative ambiguities. Rafelson’s direction, though bolstered by László Kovács’ stark cinematography, occasionally meanders—most notably in a gratuitous subplot involving two hitchhikers (one played by Helena Kallianiotes), whose diatribes feel contrived, serving only to accentuate Bobby’s relatability by contrast. The tonal shift between Tammy Wynette’s country melancholia and the Dupea family’s Chopin-infused elitism underscores Bobby’s cultural schizophrenia, yet the juxtaposition sometimes strains coherence.

The film’s conclusion—a masterclass in New Hollywood bleakness—sees Bobby abandoning Rayette at a gas station, fleeing northward into anonymity. This ambiguous ending rejects closure, mirroring the disillusionment of a generation that dismantled societal norms only to find itself unequipped to rebuild. Rafelson’s refusal to romanticise Bobby’s journey resonates as a poignant critique of Boomer idealism, capturing the void left by shattered traditions.

Five Easy Pieces remains a landmark of American cinema, albeit one tinged with imperfections. Its power derives largely from Nicholson’s career-defining turn, which elevates Bobby from a mere misanthrope to a tragic emblem of existential drift. While the film’s pacing and narrative detours have aged unevenly, its exploration of class, identity, and disillusionment retains a raw immediacy. In Bobby Dupea, Rafelson and Nicholson crafted a protagonist who embodies the contradictions of his time—a man perpetually in motion, yet going nowhere, a rebel without a cause in an age of shattered utopias.

RATING: 6/10 (++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Posted Using INLEO