The Sacrifice (1986): a masterpiece of visual poetry | una obra maestra de la poesía visual

Andrei Tarkovsky was one of the most acclaimed film directors of the 20th century and to this day his films are treated as works of cult. Although Russian cinema in general is different from what we are used to seeing on this side of the world, Tarkovsky's way of filming and writing his stories was even more particular. Hence, one can talk about his personal stamp in the same way as one talks about other great names such as Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, Orson Welles, Federico Fellini or Agnès Varda, to name just a few.

Andrei Tarkovsky fue uno de los directores de cine más aclamados del siglo XX y hasta el día de hoy sus películas son tratadas como obras de culto. Si bien el cine ruso en general es diferente de lo que acostumbramos a ver de este lado del mundo, la forma que tenía Tarkovsky de filmar y escribir sus historias era aún más particulares. De allí que se pueda hablar de su sello personal de la misma forma en que se habla de otros grandes nombres como Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, Orson Welles, Federico Fellini o Agnès Varda, por nombrar sólo unos pocos.

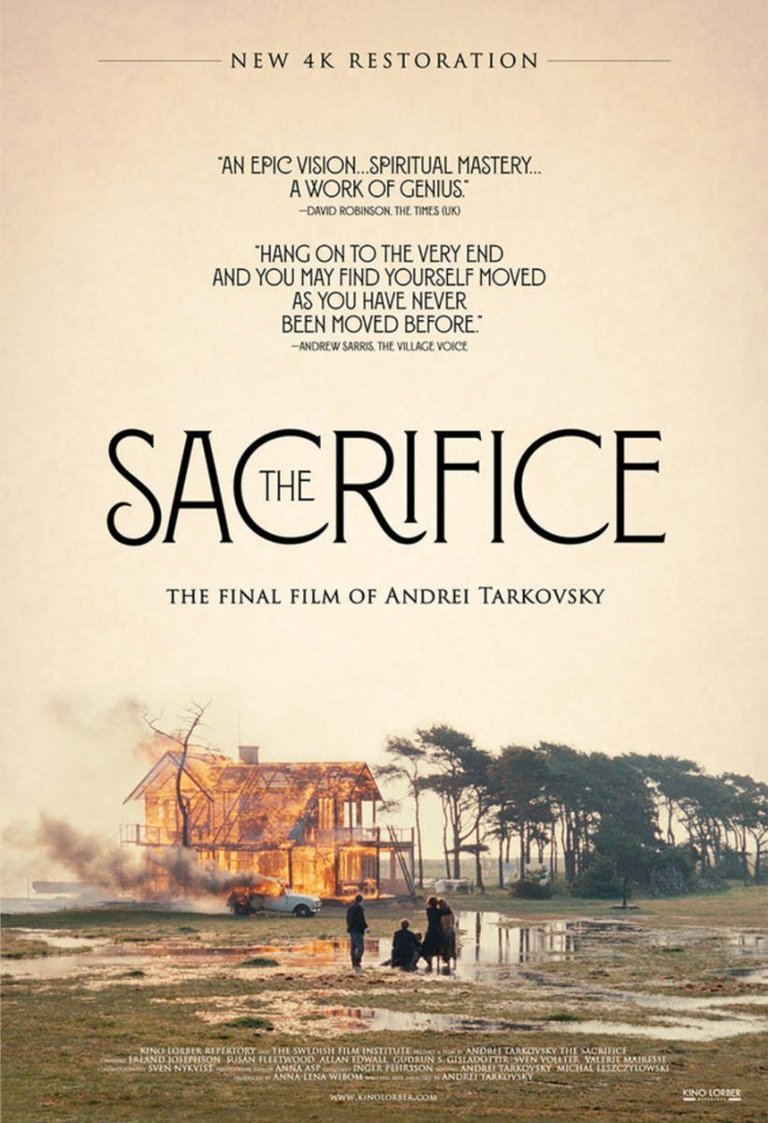

However, despite knowing this, despite admiring several Russian film directors and despite having loved my three previous encounters with Tarkovsky (Stalker, The Mirror and Solaris), I had not visited anything else from his filmography for a long time. Fortunately, a few days ago MUBI uploaded to its platform a restored 4K version of Offret (The Sacrifice), what was the last film of the great Russian director, a Swedish production (filmed in Swedish, English and French ) which has been seen as Andrei's own testament. As in other of his films, in Offret there is not such an elaborate plot or, in other words, not many things happen. That is, it's not that nothing happens, because things do happen, but that its structure doesn't focus so much on the actions of its characters, but rather on reflections on various topics. When I think of cinematic dialogues or monologues about life, death, God, the meaning of life and other related topics, several films by Ingmar Bergman come to mind, but along with them I also think of some Tarkovsky characters who seem tormented by these questions. In The Sacrifice the story centers on Alexander, a former theater actor turned critic who - in the midst of a personal crisis - feels upset by the lack of spirituality in the modern world and the imbalance that exists between material and spiritual development in a society where technological advances are used to do evil.

Sin embargo, a pesar de saber esto, a pesar de admirar a varios directores de cine ruso y a pesar de haber amado mis tres encuentros previos con Tarkovsky (Stalker, The Mirror y Solaris), tenía tiempo sin visitar algo más de su filmografía. Afortunadamente, hace pocos días MUBI subió a su plataforma una versión restaurada en 4K de Offret (The Sacrifice), la que fuera la última película del gran director ruso, una producción sueca (filmada en sueco, inglés y francés) que ha sido vista como el testamento del propio Andrei. Como en otras de sus películas, en Offret no hay una trama tan elaborada o, dicho de otra forma, no suceden muchas cosas. Es decir, no es que no pase nada, porque sí ocurren cosas, sino que su estructura no se centra tanto en las acciones de sus personajes, como en reflexiones sobre diversos temas. Cuando pienso en diálogos o monólogos cinematográficos sobre la vida, la muerte, dios, el sentido de la vida y otros temas afines, llegan a mi mente varias películas de Ingmar Bergman, pero a la par de ellas también pienso en algunos personajes de Tarkovsky que parecen atormentados por estas cuestiones. En The Sacrifice la historia de centra en Alexander, un ex actor de teatro reconvertido a crítico que - en medio de una crisis personal - se siente contrariado por la falta de espiritualidad del mundo moderno y del desequilibrio que existe entre el desarrollo material y el espiritual en una sociedad en donde los avances tecnológicos son usados para hacer el mal.

Alexander gets carried away by his thoughts as he walks with his son and talks with Otto, his friend and postman, heading home where he will meet his family on the occasion of his birthday. But shortly after being there and having dinner almost ready, the critic's worst fears are confirmed when they hear some planes passing very close to their roof and the television shows a horrifying announcement: a new large-scale war has begun. It is, possibly, World War III. And this time, the war is nuclear. Hence, everyone present, Alexander, his wife Adelaide, his stepdaughter Martha, Otto and Viktor, a family friend and doctor, feel that the end is near.

Alexander se deja llevar por sus pensamientos mientras camina con su hijo y conversa con Otto, su amigo y cartero, dirigiéndose a casa en donde se reunirá con sus familiares con motivo de su cumpleaños. Pero poco después de estar allí y de tener la cena casi lista, los peores temores del crítico se confirman cuando escuchan unos aviones pasar muy cerca de su tejado y la televisión muestra un anuncio espeluznante: ha iniciado un nuevo conflicto bélico de gran escala. Se trata, posiblemente, de la Tercera Guerra Mundial. Y esta vez, la guerra es nuclear. De allí que todos los presentes, Alexander, su esposa Adelaide, su hijastra Martha, Otto y Viktor, un amigo y doctor de la familia, sientan que el fin está cerca.

To measure this concern, we must understand the historical context. After the Second World War that devastated Europe, and in the middle of the Cold War (that arms race between the US and the USSR that led them to develop weapons unprecedented in the history of humanity) there was great tension and great fear that a new conflict between the two powers will be carried out with nuclear weapons, which could lead to global devastation. For added drama, the film was released in May 1986, just a week after the Chernobyl disaster, so Adelaide's nervous breakdown is more than justified. Faced with such a situation and the protagonist being a man so sensitive to these issues, he's presented with the opportunity to reverse the present, to sacrifice himself to change this disastrous present. Alexander doesn't hesitate and follows Otto's advice, who leads him to a character who can help him save the world. Despite presenting very few characters, their personalities have been constructed with the purpose of enriching the discussions that occur throughout the film: Alexander is the artist, the reflective philosopher; Viktor is the man of science; Otto represents beliefs in the supernatural; Adelaide is the Woman; Martha is youth, irreverence; Julia, the servant, is home, feelings; Maria, the other servant, somehow represents the sacred; and the child, who has no name, is hope, future.

Para dimensionar esta preocupación, hay que entender el contexto histórico. Después de la segunda guerra mundial que desoló Europa, y en medio de la guerra fría (esa carrera armamentística entre los EEUU y la URSS que los llevó a desarrollar armamento sin precedentes en la historia de la humanidad) existía una gran tensión y un gran temor de que un nuevo conflicto entre las dos potencias se realizará con armas nucleares, lo que podía conducir a una devastación mundial. Para mayor dramatismo, la película se estrenó en mayo de 1986, apenas una semana después del desastre de Chernóbil, así que el colapso nervioso de Adelaide está más que justificado. Ante tal situación y siendo el protagonista un hombre tan sensible a estos temas, se le presenta la oportunidad de revertir el presente, de sacrificarse para conseguir cambiar ese nefasto presente. Alexander no duda y sigue el consejo de Otto, quien lo conduce a un personaje que puede ayudarle a salvar el mundo. A pesar de presentar muy poco personajes, sus personalidades han sido construidas con la finalidad de enriquecer las discusiones que se presentan a lo largo de toda la película: Alexander es el artista, el filósofo reflexivo; Viktor es el hombre de las ciencias; Otto representa las creencias en lo sobrenatural; Adelaide, es la mujer; Martha es la juventud, la irreverencia; Julia, la sirvienta, es el hogar, los sentimientos; Maria, la otra criada, de alguna manera representa lo sagrado; y el niño, que no tiene nombre, es la esperanza, el futuro.

Offret reflects on many themes: life, death, evil in man, the soul of the artist, the separation between the artist and his art (except in the case of actors, whom Alexander considers which are their own work), the threat of the end of the world, chance, destiny, the weight of decisions, love, truth and many others. Hence, most of the scenes are dialogues or extended monologues about all these things, which in the hands of many other directors could result in a boring film. Not so in the case of Tarkovsky.

Offret reflexiona sobre muchos temas: la vida, la muerte, la maldad en el hombre, el alma del artista, la separación entre el artista y su arte (excepto en el caso de los actores, a quienes Alexander considera que son su propia obra), la amenaza del fin del mundo, el azar, el destino, el peso de las decisiones, el amor, la verdad y muchos otros. De allí que la mayoría de las escenas sean diálogos o monólogos extensos sobre todas estas cosas, lo que en manos de muchos otros directores podría resultar en una película aburrida. No así en el caso de Tarkovsky.

Because the Russian director knows how to frame that background in a captivating way. There's a lot of talk about Tarkovsky time, those prolonged scenes without cuts (the film has just over 100 scene cuts in its 145 minutes of duration and the opening sequence is a continuous take of more than 9 minutes) where the camera makes a continuous movement, it moves away, gets closer, or walks, so that the characters enter and leave the frame as the scene develops almost as if we were there. By immersing us in a scene without making cuts, Tarkovsky takes us inside that space in real time and that has an impact on the viewer who sometimes forgets that he's watching a film and not experiencing a scene. The Sacrifice, filmed in Sweden, featured Sven Nykvist on cinematography and Anna Asp on production design (both previous collaborators of Ingmar Bergman) and I was happy to see - in a supporting role - Valérie Mairesse (Pauline in One sings, the other doesn't by Agnès Varda). With a lot of surrealism, existentialism, religious iconography, wonderful photography, black and white sequences that are symbolic, a final sequence with a lot of drama, metaphors or symbols that don't always seem clear (why doesn't the child speak?) and a message somewhat cryptic, Offret may be a challenging work for some, but its visual power prevails over the capacity for incomprehension of some. Just eight months after releasing the film, Tarkovsky died of cancer, making this his swan song, his testament, his last work, which is currently available to watch on MUBI, have any of you seen it? Do you know the work of Andrei Tarkovsky? I read you in the comments.

Porque el director ruso sabe enmarcar ese fondo en una forma atrapante. Se habla mucho del tiempo Tarkovsky, esas escenas prolongadas sin cortes (la película tiene poco más de 100 cortes de escena en sus 145 minutos de duración y la secuencia inicial es una toma continua de más de 9 minutos) en donde la cámara realiza un movimiento continuo, se aleja, se acerca, o camina, de manera que los personajes van entrando y saliendo del cuadro a medida que se va desarrollando la escena casi como si estuviéramos allí. Al sumergirnos en una escena sin hacer cortes, Tarkovsky nos lleva al interior de ese espacio en tiempo real y eso tiene un impacto en el espectador que a veces se olvida de que está viendo una película y no viviendo una escena. The Sacrifice, filmada en Suecia, contó con la participación de Sven Nykvist en la cinematografía y de Anna Asp en el diseño de producción (ambos previos colaboradores de Ingmar Bergman) y me alegró ver - en un papel secundario - a Valérie Mairesse (la Pauline de One sings, the other doesn't de Agnès Varda). Con mucho surrealismo, existencialismo, iconografía religiosa, una fotografía maravillosa, secuencias en blanco y negro que resultan simbólicas, una secuencia final de mucho drama, metáforas o símbolos que no siempre parecen claros (¿por qué no habla el niño?) y un mensaje algo críptico, Offret puede resultar una obra desafiante para algunos, pero su poder visual se impone por encima de la capacidad de incompresión de algunos. Apenas ocho meses después de haber estrenado la película, Tarkovsky murió de cáncer, lo que hace de este su canto de cisne, su testamento, su última obra, que hoy día está disponible para ver en MUBI, ¿alguno de ustedes la ha visto? ¿conocen la obra de Andrei Tarkovsky? Los leo en los comentarios.