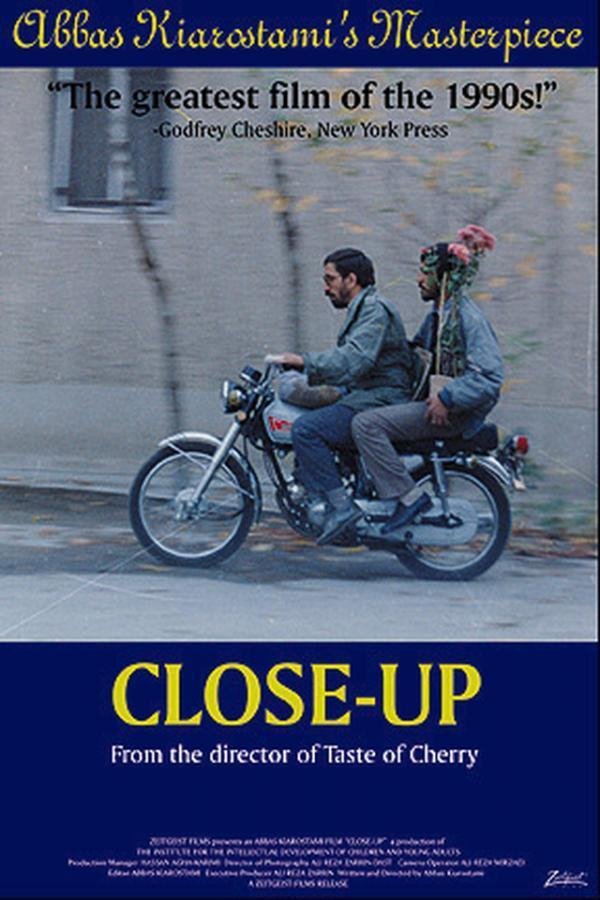

Close-Up (1990): for the love of art | por el amor al arte

We all have some particular taste. It might be a flavor of ice cream that no one else likes, a type of music that our friends don't listen to, or a genre of literature that we can't share with people we know because no one else in our circle reads it. In my case, although there is a bit of all that, I would say that my most particular taste is international cinema. Aside from Hollywood, Netflix, and the new releases that everyone is talking about, I really, really like watching movies that come from remote and unusual places on this side of the world.

Todos tenemos algún gusto particular. Puede ser un sabor de helado que no le gusta a nadie más, un tipo de música que nuestros amigos no escuchan o un género literario que no podemos compartir con la gente que conocemos porque nadie más en nuestro círculo lo lee. En mi caso, aunque hay un poco de todo eso, diría que mi gusto más particular es el cine internacional. Más allá de Hollywood, Netflix y los estrenos recientes de los que todo el mundo habla, realmente me gusta mucho ver películas procedentes de lugares remotos y poco comunes de este lado del mundo.

In that way, I like meeting Polish, Afghan, Chinese, Thai, Russian, Dutch, Australian, Indian film directors and films, etc. I feel that exposure to other times and cultures enriches my global perspective and my understanding of the soul and of the human mind. Furthermore, like literature, I believe that cinema helps to understand others, to put ourselves in their place. That is why I like to watch films by Paweł Pawlikowski (Poland), Andrey Zvyagintsev (Russia), Wong Kar-wai (Hong Kong), Asghar Farhadi (Iran) and the director who brings me here today, Abbas Kiarostami, the Iranian behind the tender Where's my friend's house?, the different Ten and the deep Taste of Cherry; three different stories from each other that share some technical traits and that give a good idea of what can be expected from this director's films: a very well written script, a simple setting, no special effects or a multi-million dollar budget. Kiarostami's cinema is a lecture for the use of resources (economic and film) and a window to the different emotions that make us human.

En ese sentido, me gusta conocer directores de cine y películas polacas, afganas, chinas, tailandesas, rusas, holandesas, australianas, indias, etc., esa exposición a otras épocas y culturas siento que enriquecen mi perspectiva global y mi entendimiento del alma y de la mente humana. Además, al igual que la literatura, creo que el cine ayuda a comprender a los demás, a ponernos en su lugar. Es por eso que me gusta ver films de Paweł Pawlikowski (Polonia), Andrey Zvyagintsev (Rusia), Wong Kar-wai (Hong Kong), Asghar Farhadi (Irán) y del director que hoy me trae hasta acá, Abbas Kiarostami, el iraní detrás de la tierna Where's my friend's house?, la diferente Ten y la profunda Taste of Cherry; tres historias diferentes entre sí que comparten algunos rasgos técnicos y que dan una buena idea de lo que puede esperarse de las películas de este director: un guión muy bien escrito, un entorno sencillo, nada de efectos especiales ni un presupuesto multimillonario. El cine de Kiarostami es una cátedra de aprovechamiento de recursos (ecónomicos y fílmicos) y una ventana a las diferentes emociones que nos hacen ser humanos.

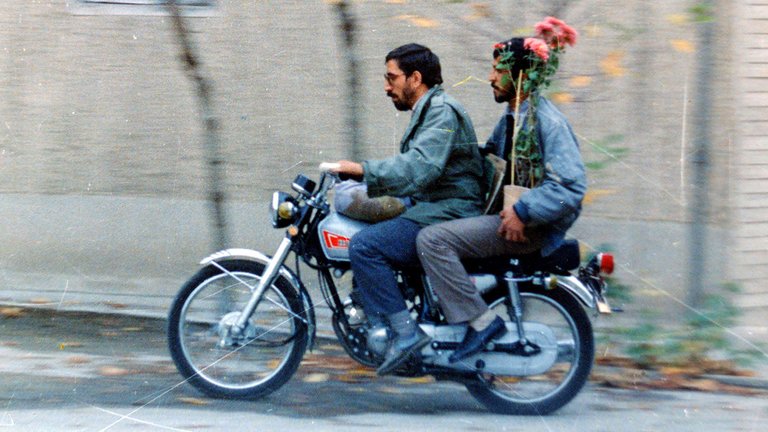

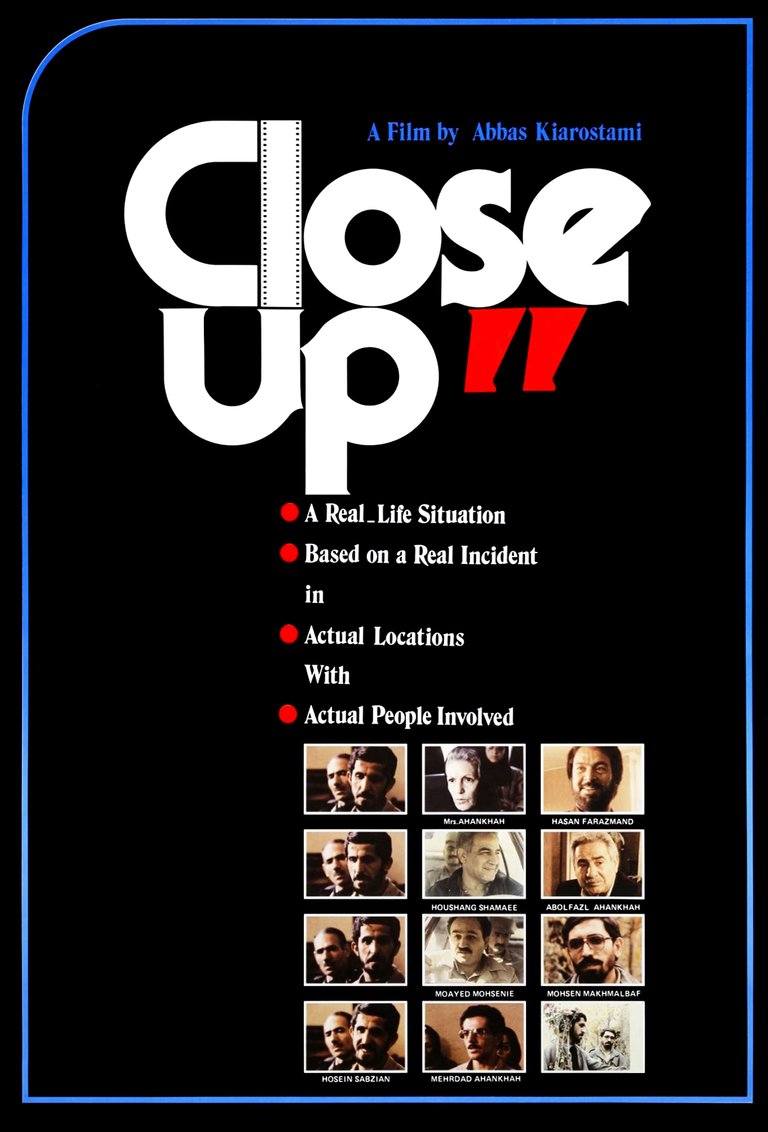

In Close-Up, Kiarostami tells the story of Hossain Sabzian, a man with a passion for cinema who for a few days posed as director Mohsen Makhmalbaf in front of a family who he indicated would be in his next film. He even told them that they were going to film it there in their house, something that did not happen because the family discovered that this man was not who he pretended to be and reported him to the authorities, which is why Sabzian was arrested and prosecuted.

En Close-Up, Kiarostami cuenta la historia de Hossain Sabzian, un hombre apasionado al cine que durante algunos días se hizo pasar por el director Mohsen Makhmalbaf frente a una familia a la que indicó que participarían en su próxima película. Incluso, les dijo que iban a filmarla allí en la casa de ellos, algo que no ocurrió porque la familia descubrió que este hombre no era quien pretendía ser y lo denunció ante las autoridades, razón por la cual Sabzian fue arrestado y enjuiciado.

And it was precisely while this man was awaiting trial that Kiarostami knew of his case from an article he read in a magazine. I mean, this story is a true story. After obtaining authorization from the judge to film Sabzian's trial, the Iranian director also managed to get both the defendant and the family who had denounced him to agree to act in the film to recreate the events leading up to the trial. That is to say, there are no actors as such because the people we see on the screen play themselves during the scenes (with the exception of the trial, in which there is no kind of acting or recreation) and this mixture of fiction and reality produces what we could call a documentary fiction that is so honest and so immediate that it quickly involves us in the case and its dilemmas: why did Sabzian do it? What led him to pretend, in front of some strangers, that he was a film director that he himself admired? Was it a scam or robbery attempt as some family members thought? The answers are not so simple, but as we listen to the defendant's testimony, we understand that he is not a bad person, that although he deceived, he did not seek to deceive (although it sounds contradictory) and we understand why he asks for forgiveness in the human sense knowing that he should be punished in the legal sense.

Y fue precisamente mientras este hombre estaba esperando por su juicio que Kiarostami se enteró de su caso por un artículo que leyó en una revista. Es decir, esta historia es una historia real. Tras obtener la autorización del juez para filmar el juicio de Sabzian, el director iraní consiguió además que tanto el acusado como la familia que lo había denunciado aceptaran actuar en la película para recrear los acontecimientos previos al juicio. Es decir, no hay actores como tal porque las personas que vemos en pantalla se interpretan a sí mismos durante las escenas (a excepción del jucio, en el cual no hay ningún tipo de actuación o recreación) y esta mezcla de ficción y realidad produce lo que podríamos denominar una ficción documental que resulta tan honesta y tan inmediata que nos involucra rápidamente en el caso y en sus dilemas: ¿por qué lo hizo Sabzian? ¿qué lo llevó a fingir, frente a unos desconocidos, que él era un director de cine que además él mismo admiraba? ¿era un intento de estafa o de robo como pensaron algunos miembros de la familia? Las respuestas no son tan sencillas, pero a medida que oímos el testimonio del acusado vamos entendiendo que no es una mala persona, que si bien engañó, no buscaba engañar (aunque suene contradictorio) y comprendemos por qué pide perdón en el sentido humano sabiendo que debe ser castigado en el sentido legal.

Close-Up deals with universal themes such as human identity, self-realization, the concept of art, love of cinema, but it does so within the specific framework of Iranian culture, creating a very interesting mix. The script - because even if it is based on things that happened, you still have to write a script - is by Kiarostami himself, who not only appears in the film but also took charge of the photography in which there are many close-ups, the talks in the closed spaces and the transmission of emotions through the faces of those who intervene. At just under a hundred minutes long, Close-Up is a study of the human soul and identity, which will make us think hard about repentance, redemption, and forgiveness. On the other hand, the idea that Kiarostami had to end the film was incredible and that final sequence is one of the most emotional I've seen in any film. Who among you has seen a story by Abbas Kiarostami? Do you know anything about Iranian cinema? I read you in the comments.

Close-Up trata temas universales como la identidad humana, la auto realización, al concepto del arte, el amor al cine, pero lo hace en el marco específico de la cultura iraní, creando una mezcla muy interesante. El guión - porque aunque se base en cosas que ocurrieron igual hay que escribir un guión - es del propio Kiarostami, quien no sólo aparece en el film sino que también se encargó de la fotografía en la que abundan los primeros planos, las charlas en los espacios cerrados y la transmisión de emociones a través de los rostros de quienes intervienen. Con poco menos de cien minutos de duración, Close-Up es un estudio del alma humana y la identidad, que nos hará pensar mucho en el arrepentimiento, la redención y el perdón. Por otro lado, la idea que tuvo Kiarostami para terminar la película fue increíble y esa secuencia final resulta de las más emotivas que he visto en película alguna, ¿quién de ustedes ha visto alguna historia de Abbas Kiarostami? ¿conocen algo del cine iraní? Los leo en los comentarios.

Reviewed by | Reseñado por @cristiancaicedo

Other posts that may interest you | Otros posts que pueden interesarte:

|

|---|

Que esperas para unirte a nuestro trail de curación y formar parte del "proyecto CAPYBARA TRAIL", se despide Capybaraexchange tu casa de cambio, rápida, confiable y segura

Ya que te gustan las películas independientes, te recomiendo las brasileras, son buenísimas.

Fíjate que he visto pocas, pero me ha gustado. Una de mis favoritas es Ciudad de Dios y tengo en lista una llamada Central Station, ¿conoces algunos títulos específicos que puedas recomendarme? Saludos

Gracias por tus recomendaciones ☺️